Unlocking the Genetic Code Behind Pain Sensitivity

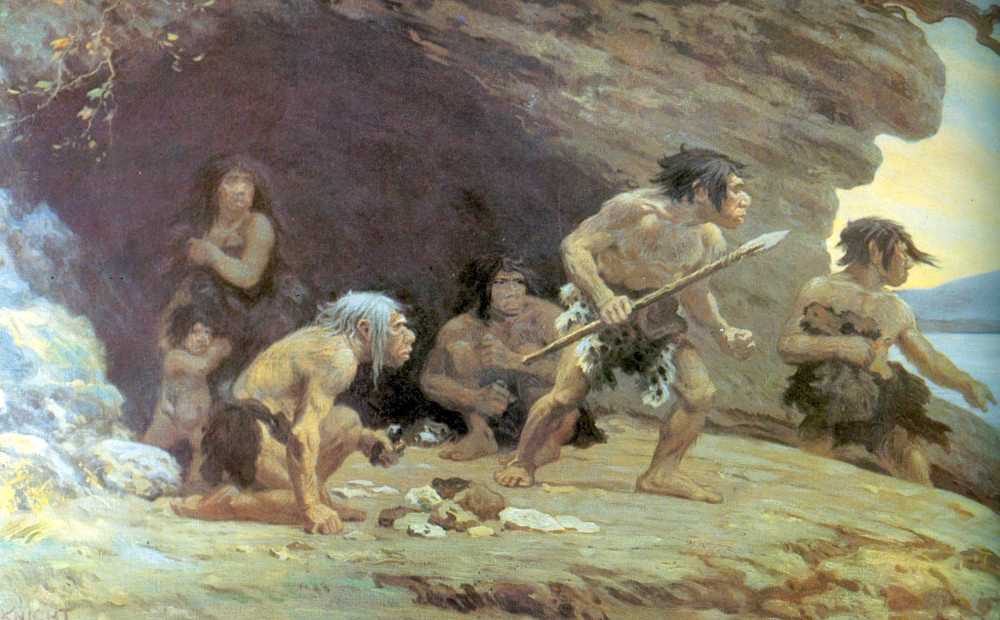

In the world of genetic analysis, an intriguing revelation has emerged: your sensitivity to pain might be influenced by your Neanderthal DNA. This captivating discovery, born from the meticulous scrutiny of genetic samples collected from over 7,000 individuals, has linked three specific genetic variants inherited from Neanderthals to heightened pain sensitivity.

Decoding the Connection Between Neanderthal DNA and Modern Human

Recent research highlights that these Neanderthal DNA and genetic variants have the potential to amplify pain sensitivity in those who carry them, and they are particularly prevalent among populations with Native American ancestry.

This groundbreaking study, published in Communications Biology, delves into the SCN9A gene, responsible for encoding a protein that aids in the transmission of signals in nerve cells, allowing us to perceive pain. The focus here is on three versions of this gene. Individuals possessing any of these three variants tend to be more sensitive to the sharp, piercing pain induced by a needle but not necessarily to heat or pressure-related pain.

Pierre Faux, the lead author of the study and a geneticist at the French National Institute for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment, explains, “In 2020, another research group examined individuals of European origin and linked these Neanderthal DNA variants to increased pain sensitivity. By studying Latin Americans, we have expanded these findings, demonstrating that these Neanderthal genetic variants are far more common among individuals of Native American descent. Additionally, we have identified a previously unknown type of pain influenced by these variants.”

A Pan-American Genetic Odyssey

The study saw scientists analyzing genetic samples from over 5,900 individuals residing in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. The participants represented a diverse mix, with an average of 46% Native American, 49.6% European, and 4.4% African ancestry. However, these percentages exhibited significant variability among individuals.

The analysis revealed that approximately 30% of participants carried one of the SCN9A gene variants known as D1908G, while roughly 13% exhibited a tendency to inherit the other two gene variants, V991L and M932L, which are considered hereditary.

Among the countries studied, participants from Peru, where Native American ancestry is most prominent, had a higher likelihood of carrying these Neanderthal genetic variants. In contrast, participants from Brazil, with the lowest Native American ancestry, had the lowest likelihood of carrying these variants.

Faux elaborates on the historical context, saying, “We know that modern humans interbred with Neanderthals approximately 50,000 to 70,000 years ago, and it was only 15,000 to 20,000 years ago that modern humans first migrated from Eurasia to the Americas. The high frequency of Neanderthal variants among individuals with Native American ancestry may potentially be explained by the scenario in which these Neanderthals, carrying these variants, mated with the modern humans who would later migrate to the Americas.”

Putting Pain to the Test through the Neanderthal DNA Effect

Following genetic analysis, researchers conducted pain threshold tests on over 1,600 volunteers in Colombia. Of these volunteers, 56% were female, 31% had Native American ancestry, 59% had European ancestry, and 9.7% had African ancestry. In these tests, participants were asked to indicate when they felt discomfort. The researchers also analyzed the genetic variants carried by each participant.

In one of the tests, the researchers applied mustard oil to the forearm of the participants, causing irritation before pushing wider plastic filaments onto the same area of irritated skin. Participants with any of the Neanderthal gene variants stopped the test much sooner than those without the variants, demonstrating heightened sensitivity to the type of pain caused by needle pricks.

Faux emphasizes, “When we tested participants’ pain thresholds using pressure, heat, or cold, we found that the gene variants did not affect pain sensitivity. Thus, we observed that the Neanderthal variants exclusively influenced the response to the pressure of a needle prick.”

The Possibility of Survival Advantage

According to Faux, carrying these gene variants may have conferred a survival advantage to Neanderthals and the early humans who settled in America. However, it’s important to note that this survival benefit may not necessarily be related to pain sensitivity.

The first humans who ventured into North America had to endure harsh and cold conditions. Therefore, these gene variants might have had effects beyond pain sensitivity. They could have, for instance, aided in coping with the cold. In other words, heightened sensitivity to sharp objects might just be a side effect of another evolutionary change.

However, the evolutionary pressures acting on SCN9A were likely complex, and the reasons why Neanderthals might have had greater pain sensitivity and whether the introgression in SCN9A offered an advantage during human evolution remain to be determined.