A long-abandoned waka, the traditional canoe of the Maori people, was recently discovered in the shallow waters of the Patea River in the Taranaki region of western New Zealand. With its estimated age exceeding 150 years, locals believe it was deliberately concealed by their Maori ancestors to protect it from seizure by the British colonial government during the 19th century.

Identifying the Maori Waka Canoe

The remarkable discovery was made by several Maori individuals as they strolled along the riverbanks. The waka, firmly entrenched in the mud, was easily recognizable by its long, graceful silhouette.

“To us, it was found because of this kōrero [conversation] about a tohu [a sign] that happened about three weeks ago when tuna were found on the beach at Te Patea,” shared Ngapare Nui, a local Maori elder, with Te Ao Maori News. “They had to find out how our taonga [valuable treasure] passed away… they came up here and they were looking to see if there was any more dead tuna along the river here, and that’s when they came across the taonga, the waka here.”

Shortly after its discovery, the Ministry of Culture and Heritage was notified and initiated an investigation. “As soon as I saw it, I knew it was a waka from the old people because it was made of totara,” revealed South Taranaki Maori historian Darren Ngarewa in an interview with New Zealand’s 1 News.

Ngarewa further explained that wakas were traditionally constructed from the totara tree, a native species in New Zealand known for its light weight and resistance to rotting and splitting. The use of totara wood for this particular waka unveiled its true origin.

Recovering a Maori Waka Hidden During New Zealand Wars

In the 19th century, the southern region of Taranaki was inhabited by three Maori iwi: Te Pakakohi, Ngati Ruanui, and Nga Rauru (Darren Ngarewa belonged to the Ngati Ruanui iwi). During this time, these groups were at odds with the British colonial government of New Zealand, which was eager to seize Maori lands for incoming British farmer-settlers.

In 1869, a significant event known as the New Zealand Wars or Maori Wars took place, leaving a lasting impact on the modern Maori living in the area. During a raid in that year, colonial forces captured the highly respected Maori chief Ngawaka Taurua along with several iwi elders.

These individuals were subsequently imprisoned in a concentration camp in Otago, where many other captured Maori warriors and civilians were also held. Unfortunately, the overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in the camp led to a high casualty rate among the indigenous people.

Apart from other atrocities, the colonial forces confiscated or destroyed any wakas they came across to restrict Maori warriors’ freedom of movement by water. The Maori who stumbled upon the waka in the Patea River believe that locals intentionally hid it around 1869 to safeguard it from falling into the wrong hands.

It is possible that they planned to retrieve the long canoe later, but for reasons unknown, it remained concealed in the shallow river waters for over a century and a half until its recent discovery.

“We have spent so long reclaiming ourselves after so much interference by the Crown so to rediscover a part of our missing history, particularly on the 154th anniversary, is big for us,” expressed Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, a leader of the local Ngati Ruanui iwi.

“This is not something we talk about because of the pain we suffered,” Ngarewa added. “But with the waka coming out and the way it was coming out, it was unfolding as part of a bigger picture. Now maybe is the time to tell our story.”

The Story of the Waka, an Indispensable Maori Innovation

The history of the waka is intrinsically intertwined with the history of the Maori people in New Zealand. The original Polynesian Maori settlers arrived in New Zealand between 1250 and 1300, and it was the waka that served as their vessels during this migration.

The oldest ancient waka ever recovered in New Zealand dates back to approximately the year 1400, while other discoveries generally range from the 16th to the mid-19th centuries. Interestingly, ancient canoes found on various Polynesian islands bear striking similarities to the Maori waka, confirming that the Maori brought this technology with them during their migration.

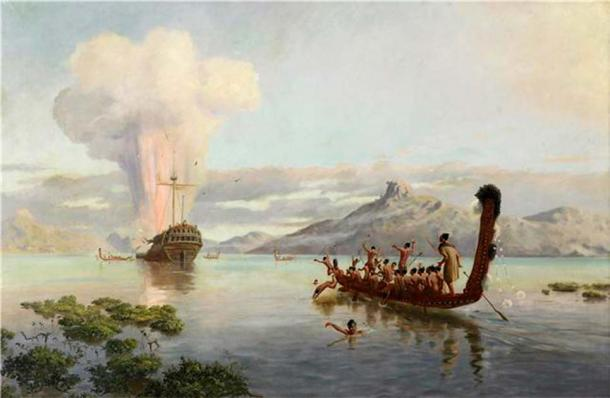

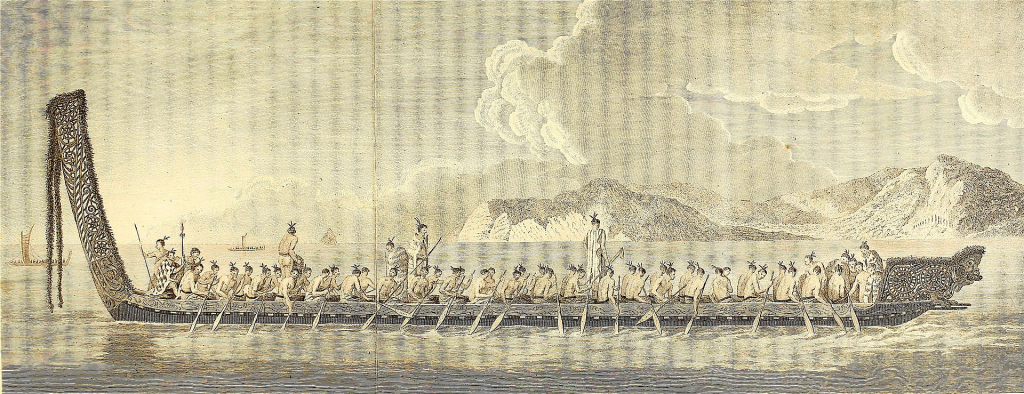

The interior of the waka was painstakingly carved out of an intact totara log, which could weigh as much as three or four tons in some cases. Using stone tools, the entire process of carving, shaping, and finishing the waka canoe could take up to a year or more to complete. The crafts were often elaborately decorated and painted, displaying cultural images that held significant meaning to the different iwi involved in their construction.

Wakas varied in size, from small crafts suitable for navigating tight rivers to 130-foot (40-meter)-long canoes designed for warfare or ocean travel. The larger wakas could accommodate up to 80 paddlers, and the Maori often attached temporary sails for maximum speed when traversing the waters of the Pacific.

In regions like Taranaki, wakas were indispensable, serving purposes such as inland travel along rivers, ocean travel along coastlines, fishing, and harvesting various marine life. They also played a critical role in ancient naval operations, as Maori seaborne patrols were dispatched to protect coastal communities from external invaders.

Proud Culture and Tragic History Revealed by Canoe

While the use of wakas declined during the last 150 years, the Maori people still regard them as a foundational technology that significantly influenced their culture’s development. Hence, the recent discovery has sparked immense excitement among the inhabitants of the Taranaki region, who have been part of this rich cultural heritage for 700 years.

After being laboriously extracted from the mud by a dedicated team of locals, the newly salvaged waka was airlifted by helicopter to the city of New Plymouth for restoration. No final decision has been made regarding the canoe’s fate.

The iwi of Taranaki hopes to exhibit the waka near its original discovery site, using it as an educational tool to impart knowledge about their cultural roots and the harrowing oppression endured by the Maori during the violent New Zealand Wars. “This is much bigger than just us, for the hapu [Maori clans] and iwi,” emphasized Ngarewa.