In the annals of history, few practices have captured the imagination and curiosity of the world as much as Seppuku, the ritual suicide that originated in Japan’s ancient warrior class. Often referred to as “hara-kiri” in the Western world, this ancient custom is a fascinating blend of honor, ceremony, and tragedy. Join us on a journey through time as we delve into the intricate details of this remarkable practice.

The Origins of Seppuku

Seppuku, deeply rooted in Japan’s feudal history, emerged during the 12th century as a solemn means for samurai to attain an honorable death. The act itself was a gruesome one, involving the individual stabbing their belly with a short sword, thereby opening their stomach, before turning the blade upwards to ensure a fatal wound.

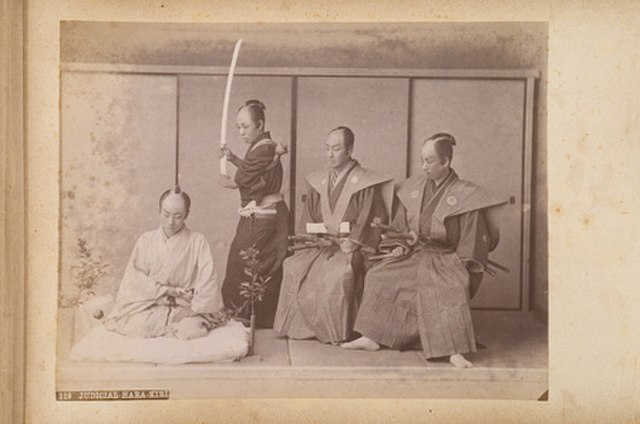

The Role of the “Kaishakunin”

While some practitioners of seppuku allowed themselves to endure a slow and agonizing death, many sought assistance from a “kaishakunin” or second. The kaishakunin’s role was to swiftly decapitate the individual with a katana as soon as they made their initial self-inflicted wound. This macabre process was not undertaken lightly and was steeped in elaborate ceremony.

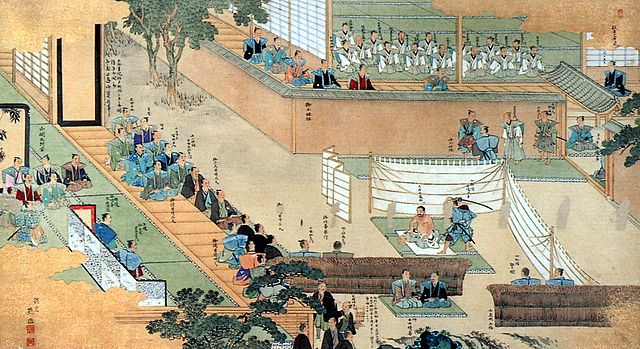

The Ritual and the “Death Poem”

Before embarking on this ultimate act of self-sacrifice, the doomed individual often partook in rituals that included consuming sake and composing a short “death poem.” These poems served as poignant expressions of their emotions and reflections in the face of mortality, adding a layer of depth to the ritual.

A Protest and a Grief-Stricken Tribute

Seppuku served multiple purposes beyond its initial role as an honorable death. Samurai would sometimes perform the act to avoid capture following battlefield defeats, effectively choosing their own fate over potential humiliation. Additionally, it became a powerful form of protest and an outlet for expressing grief over the death of a revered leader.

Evolution into Capital Punishment

As Japan’s history unfolded, seppuku evolved into a common form of capital punishment for samurai who had committed crimes. Each instance of this practice was viewed as an act of extreme bravery and self-sacrifice, embodying the principles of Bushido, the ancient warrior code of the samurai. Remarkably, there even existed a female version of seppuku known as “jigai,” which involved cutting the throat with a special knife called a “tanto.”

The Twilight of Seppuku

With the decline of the samurai in the late 19th century, seppuku began to fade from prominence. However, it did not completely vanish from history. Notable instances, such as Japanese General Nogi Maresuke’s self-disembowelment in 1912 as an act of loyalty to the deceased Meiji Emperor, and the choice of many troops to wield the sword rather than surrender during World War II, showcase its enduring legacy.

Yukio Mishima: A Modern Tragedy

One of the most famous cases in recent history involves Yukio Mishima, a renowned novelist and Nobel Prize nominee. In 1970, Mishima led a failed coup against the Japanese government and, in a final act of conviction, committed ritual seppuku. His story is a poignant reminder of the enduring significance of this ancient practice.

Conclusion

Seppuku, a ritual suicide that defined the ethos of Japan’s ancient warrior class, is a complex tapestry of honor, courage, and tradition. Its evolution from a means of honorable death to a form of capital punishment mirrors the ever-changing landscape of Japanese history. Though largely relegated to the annals of history, its legacy endures, a testament to the enduring spirit of the samurai.