Nüshu is a unique and fascinating syllabic script derived from Chinese characters that had a singular purpose – it was used exclusively among women in Jiangyong County, located in the southern province of Hunan, China.

Characteristics of Nüshu

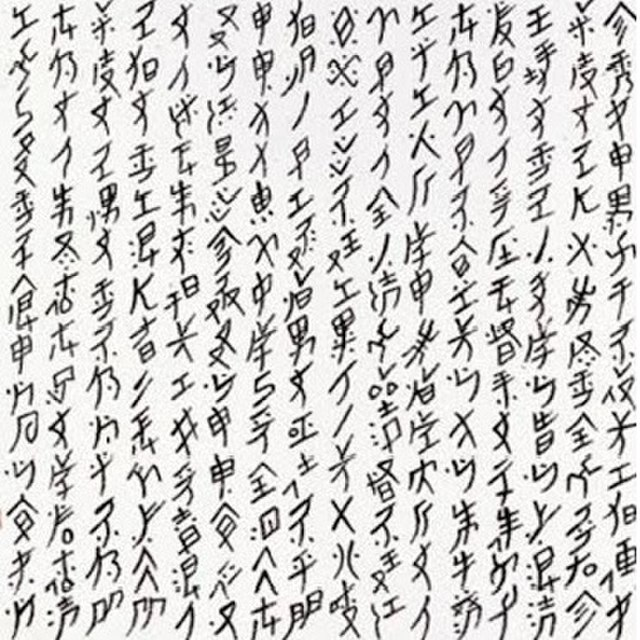

In contrast to standard written Chinese, which follows a logographic system where each character represents a word or part of a word, th language operates on a phonetic basis. Each of its approximately 600-700 characters represents a syllable. This revolutionary approach reduced the number of characters required to represent all syllables significantly, making it one of the most efficient simplifications of Chinese characters ever attempted. Zhou Shuoyi, the only male known to have mastered the language, compiled a dictionary listing 1,800 variant characters and allographs.

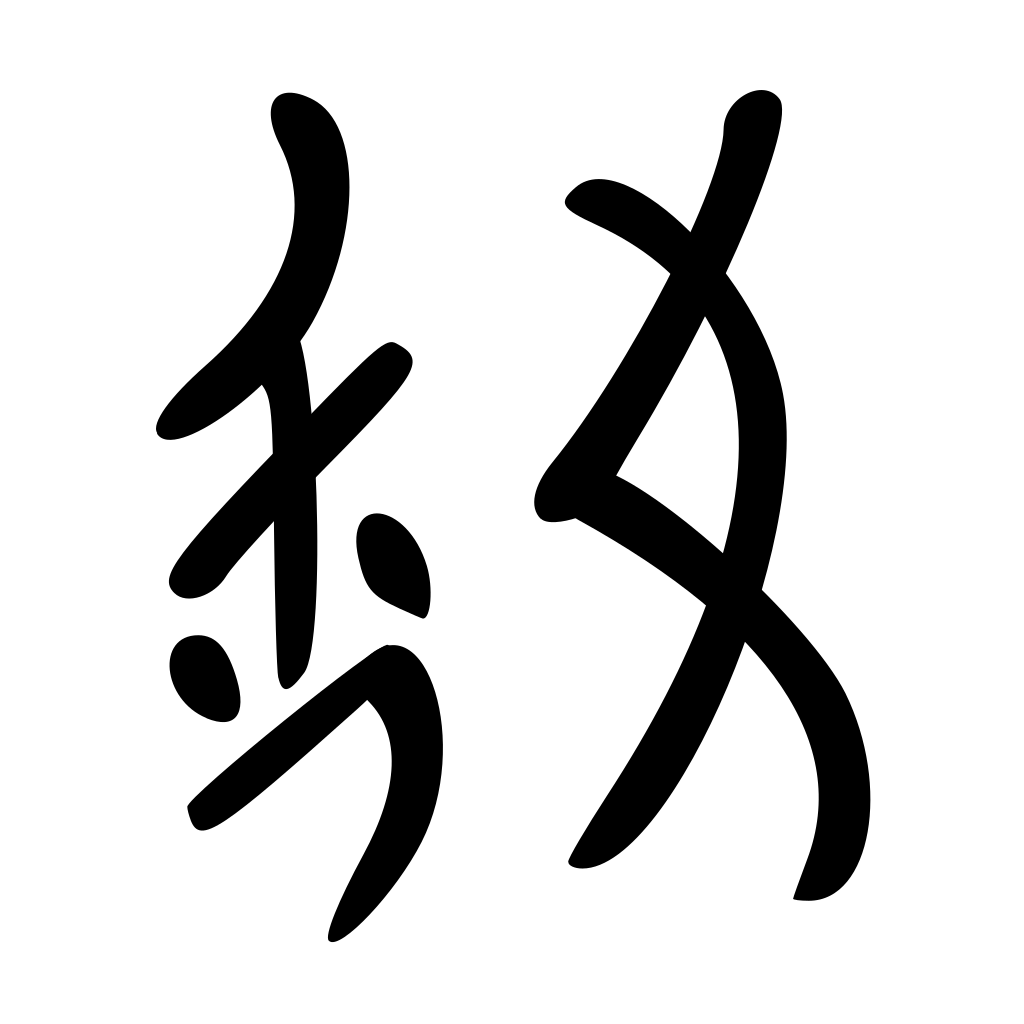

The characters of Nüshu bear a resemblance to italic variant forms of Kaishu Chinese characters. However, some have been modified to suit embroidery patterns. The strokes used in Nüshu characters consist of dots, horizontals, virgules, and arcs. Traditionally, the script was written in vertical columns from right to left, similar to classical Chinese writing. But in modern contexts, it can also be written horizontally from left to right, much like contemporary Chinese. Writing Nüshu script with exceptionally fine, almost threadlike lines is considered a mark of exquisite penmanship.

Around half of Nüshu characters are modified Chinese characters used logographically. About 100 characters are adopted almost unchanged, with slight alterations to their frames. Another hundred have undergone some modifications but remain easily recognizable. The remaining characters are phonetic and either modified characters or elements extracted from other characters. These 130 phonetic values were used to write, on average, ten homophonous or nearly homophonous words, with some variations among different communities.

Historical Context of Nüshu

Nüshu’s history is intertwined with the traditions and customs of Jiangyong County. Before 1949, the county’s agrarian economy restricted women to follow patriarchal Confucian practices, including the Three Obediences. The practice of Nüshu developed within the context of women being confined to their homes and assigned roles in housework and needlework rather than fieldwork. Unmarried women, known as “upstairs girls,” would gather in groups to embroider and sing Nüge (women’s songs), which provided an opportunity for young women to learn the language.

The exact origin of the language is difficult to determine due to local customs of burying or burning Nüshu texts with their owners and the perishable nature of textiles and paper in humid environments. Nevertheless, many simplifications found in Nüshu were informally used in standard Chinese since the Song and Yuan dynasties. Its peak usage was during the latter part of the Qing dynasty.

The Decline and Preservation Efforts

As societal changes occurred in the 20th century, with wider access to literacy in Chinese characters, younger girls and women gradually stopped learning the language. This led to its decline as older users passed away. The language also faced suppression during Japan’s invasion of China and the Cultural Revolution.

In the 21st century, Nüshu’s preservation efforts gained momentum. Yang Huanyi, the last proficient user of the language, passed away in 2004. To safeguard Nüshu as an intangible cultural heritage, a Nüshu museum was established in 2002, and “Nüshu transmitters” were created in 2003.

However, with the line of transmission now broken, there are concerns that the true essence of Nüshu might be distorted in marketing efforts aimed at the tourist industry.

Nüshu in Contemporary Art and Culture

The language, being largely practiced in the private sphere historically, was often overlooked in the public domain due to patriarchal ideas. Despite this, contemporary artists have attempted to preserve and commemorate Nüshu’s cultural significance through various creative expressions.

Chinese composer Tan Dun’s multimedia symphony “Nu Shu: The Secret Songs of Women” celebrates the women who communicated through Nüshu songs. Authors like Lisa See have brought Nüshu’s usage among 19th-century women to the forefront through literary works.

Contemporary artists, such as Yuen-yi Lo and Helen Lai, have used drawing and dance respectively to critique the traditional separation between writing and drawing and challenge the patriarchal media representation of the language. Their efforts highlight Nüshu as an innovative art form that deserves recognition beyond being considered a mere “secret.”

Fantastic beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a blog website? The account aided me a acceptable deal. I had been tiny bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered bright clear concept

I do consider all the ideas you’ve introduced to your post. They’re very convincing and will definitely work. Nonetheless, the posts are too brief for newbies. Could you please prolong them a little from subsequent time? Thanks for the post.

Thank you for another informative site. Where else could I get that kind of information written in such an ideal way? I’ve a project that I am just now working on, and I’ve been on the look out for such information.

One other thing I would like to convey is that as an alternative to trying to suit all your online degree training on days and nights that you conclude work (since the majority people are worn out when they return home), try to obtain most of your lessons on the week-ends and only a couple courses in weekdays, even if it means taking some time away from your weekend. This is beneficial because on the weekends, you will be much more rested and concentrated in school work. Thx for the different ideas I have learned from your site.